New Gourna, Egypt is an internationally celebrated and recognized village for Hassan Fathy’s attempts at inclusive participatory planning. This exploration began with wanting to understand why this new village, with all its glory, failed, recognizing the breadth of research. In the creation of New Gourna we can see the reconstruction of local history as analogous with the struggle to represent a complex national identity, which led to questioning not the failure, but rather the rejection by the community of New Gourna. This led to exploring issues of westernization, national identity, and the historically marginalization people.

Concluding from this, the case of El Gourna was rather the greater failure of ‘designing for the poor’ instead of designing for the historically marginalized and under valued. Current campaigns are advocating the conservation and protection of New Gourna, however hesitancy toward celebrating this cultural and historical reconstruction comes from the discrepancies in recognizing a legitimate culture and history of the Gournis themselves. In this reconstruction, priority was given to the protection of the ancient heritage over the reality of the contemporary culture and needs. While recent attempts have been made internationally to be more conscientious towards current use and socio-cultural significance of a site in conserving an ancient history, their effectiveness has yet to be truly evaluated in changing the practice within the global culture of historical reconstruction. So, how can these seemingly disparate cultures, ancient history and the present generation, become equalized in their relevance to preserve and plan for today and tomorrow?

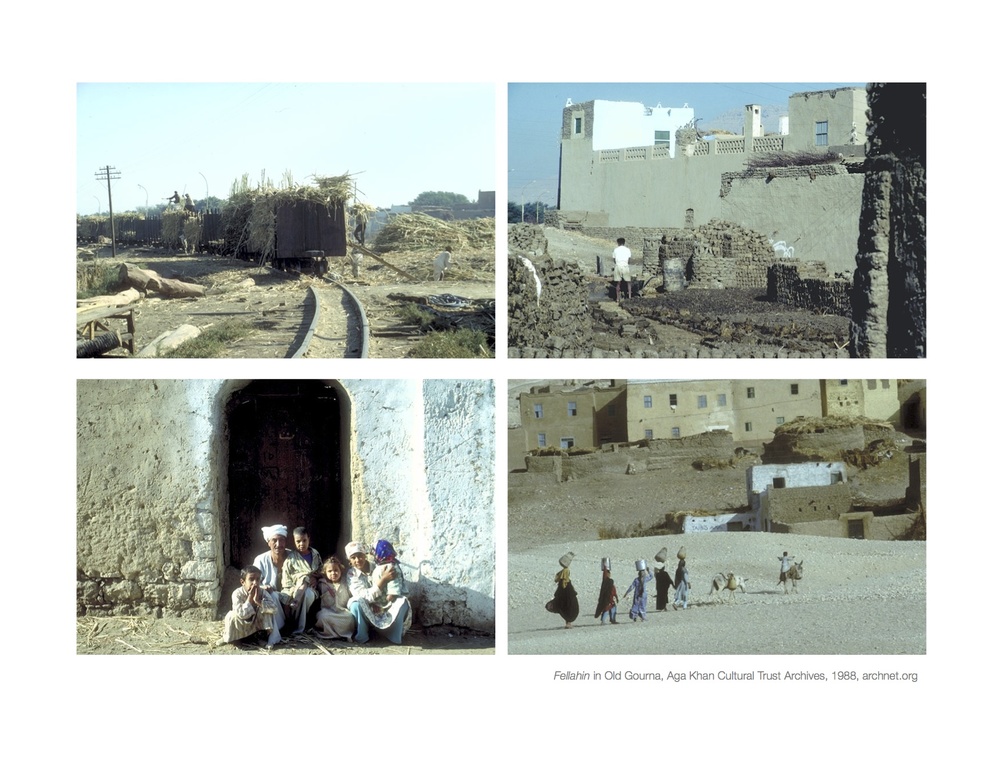

“Old Gourna Village was the impetus for Hassan Fathy’s New Gourna Village. The idea for the new village was launched by the Egyptian Department of Antiquities as a solution to the problem of relocating the entire entrenched community of entrepreneurial excavators that had established itself over the royal necropolis in Luxor. The villages resisted relocating to the new village and made every effort to stay where they were.”

“A decrepit bent-back man with a white beard come forward, hobbling on a stick. The judge pounced on him with a question: ‘You expended reserved wheat?’

‘It was my wheat, your honour, and I ate it with my family.’

‘Pleads guilty. One month with hard labour!’

‘A month! Do you hear, Muslims! My own wheat, my own crop, my own property...!’

...

Surely his ears must have deceived him and the spectators must have heard the truth. For he had stolen no man’s wheat. It is true that the usher had visited him and ‘reserved’ his wheat, appointing him as its trustee until such time as he paid the government tax. But the pangs of hunger had seized him violently – him and his family; so he had eaten his own wheat. But who could possibly regard him as a thief on that account and punish him for stealing?”

Research team: Nadia Elokdah, Nora Elmarzouky, and Kat Horstmann